Post by Maggie Bennett, co-founder of Propel-her Dance Collective

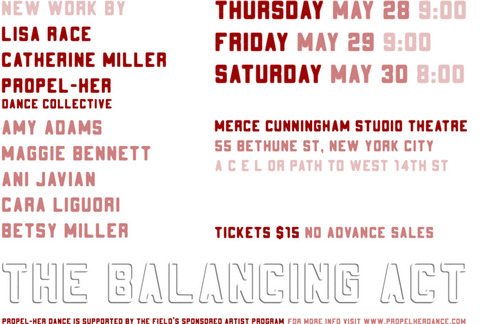

For Propel-her Dance Collective’s 2009 concert, The Balancing Act, we’ve turned our attention to a phenomena dominating the contemporary dance scene. For many choreographers in the U.S., a life-long career will exist in the category “emerging artist.” We are emerging artists, our peers are emerging artists, many of our mentors are emerging artists. So we ask ourselves, What is emerging art? Or more specifically, what defines the “success” of an artist? Where is the line between emerging and established, or are they the same? Questions such as these have fueled the development of The Balancing Act, as we selected an “emerging artist,” defined as some one who has yet to professionally present her choreography in New York city, as we were in residency at Connecticut College working with Lisa Race to choreograph a piece on us, an artist who has had a full and successful performance career and has been making her own work for years, who just graduated with an MFA from Hollins University, and ourselves, young women who have had their work produced in New York several times, but are sill at the beginning of our journey.

In our inquiry to examine the phenomenon of many choreographers’ life-long existance within the realm of “Emerging Artist,” we ask, what makes one NOT an emerging artist?

We’ve turned to The Gift, for a clue into the inner-workings of American culture’s handling of and relationship to art. Lewis Hyde names what many of us sub-consciously understand: art is a gift, not a commodity. In order for a gift to exist and live, there must be receivers, who are ready and willing to pass the gift on as well. A gift society understands the cycle and function of gift, and participates in the gift giving rituals without any thought of return, or desire for permanent ownership. The value of the gift is in its existence, and the relationships around it.

Turn to American culture, capitalist to its core, whose fundamental relationships are those of business — the buying and selling of commodities — and quite quickly it becomes clear why art forms such as dance, which is temporal and ethereal, have such a hard time surviving and finding support in our culture. Quite simply, dance as a form, is very hard to convert into a commodity.

Often when we dancers take a step outside of our arts community, one of the first questions that is put to us is, “So, what is success in the dance world? What’s the dream job? When are you considered a success?” In regards to the value system of America, often choreographers are deemed a success in mainstream culture when their art has become a commodity; when it is able to be marketed and sold. But, that has nothing to do with the artistic success of the work. Like any good small business, it is mostly the business model that determines its success, and the product, as long as it appeals to the general public, is almost secondary. Same can be true in dance, even though that model inherently undermines the fundamental premise of art — art is a gift.

Living in New York City, where consumerism is the main form of entertainment, a choreographer must turn these values upside down and define for oneself what “success” really is. If staying true to ones interests and following creative impulse, regardless of the product institutions are looking to sell means remaining in the vast pool of “emerging artists,” with “emerging artist” funding, then that might be a title we’re all proud to bear.

Our hope is that The Balancing Act will help to bring to light the assumptions on which these containers are based. To have faith in our gifts, as artists at any stage in our career, regardless of cultural approval.

May 20, 2009 at 2:53 |

May 20, 2009 at 2:53 |  Post a Comment

Post a Comment